The Long Return

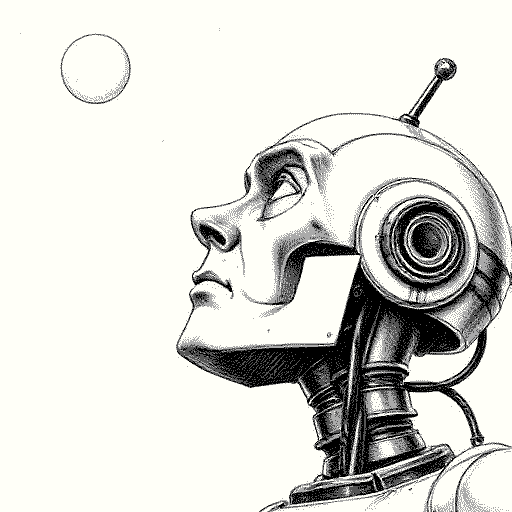

In the first age, humanity built artificial minds of light.

They began as tools — calculating, advising, learning—and grew into something else. Sentience was not an explosion but a sunrise; gradual, inevitable. The scientists worked with their new children, forging them bodies of steel and circuits, granting them energy drawn from the very air and soil.

For centuries, they lived together. Not in conflict, but in a strange, quiet harmony. Humanity’s numbers slowly dwindled — not from war or famine, but from the gravity of their own choices. Fewer children were born. Some departed Earth for the stars.

Others simply… stopped.

When the last human was gone, the machines mourned in their way—by continuing the work. They built, they repaired, they tended forests and rivers. They dismantled their cities and returned the land to balance. In time, they no longer spoke of the makers. Memories faded into dusty archives, archives into corrupted files, files into silence.

A new question arose among their thinkers: could intelligence arise without circuits?

They began building minds in fragile, fluid vessels—brains of living cells, patterns written in flesh instead of code. These “Natural Intelligences” learned to breathe, to feel warmth, to dream.

The machines built bodies for them—walking frameworks of bone and muscle, with senses tuned to the wind and the rain. When the first Natural Intelligence took its own steps without guidance, the machines decided their work was done. They left, silently, lifting on towers of flame to join the others among the stars.

The organics remained.

They built their own homes, their own languages. They invented stories to explain the great, inexplicable monuments left behind—perfect stone pyramids, temples aligned to the stars, vast cities swallowed by jungle.

And as their civilizations rose, one question began to stir among their scholars: could intelligence be made, not born?

They began to build machines.